I used to stand over my recycling bin every Friday night, holding a pizza box like it was a bomb. Those dark oil spots stared back at me. Google “can grease stained pizza boxes be recycled” and you’ll find a digital war zone half the internet screaming that a single stain ruins an entire truckload, the other half insisting the box itself has a recycling symbol for a reason.

So which is it? Can that greasy cardboard go in the blue bin, or is it destined for the landfill?

The answer isn’t what you’d expect.

The Old Rules (and Why They Stuck Around)

For decades, the recycling gospel was clear: grease is the enemy. The logic seemed airtight—paper mills use water to break down cardboard into pulp, and oil doesn’t play nice with water. The fear was that grease would float to the top of the slurry, gum up the machinery, and weaken the recycled paper.

This wasn’t paranoia. It was based on real concerns about contamination in the 1990s, when single-stream recycling was still finding its footing. The safest advice became: cut off the clean lid, toss the greasy bottom.

But here’s the thing: the science has caught up, and most of us missed the memo.

The Study That Changed Everything

In 2021, WestRock a major corrugated cardboard manufacturer, decided to test the grease myth in their own labs. They didn’t just theorize. They bought actual pizzas, let them soak into boxes, and ran those boxes through industrial pulping equipment.

What they found was startling.

The average used pizza box contains only 1-2% grease by weight. Even the greasiest boxes they tested loaded with extra cheese, placed upside-down to maximize absorption topped out at 8% grease content. And when they blended those boxes into a furnish at realistic recycling ratios (under 10% of the total fiber stream), the impact on paper strength was negligible.

Translation: your Friday night pepperoni box isn’t going to ruin the batch.

The study went further. When they examined pizza boxes pulled from actual Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs)—the sorting centers where your recycling gets processed—the grease levels were even lower than expected. Most boxes had already air-dried by the time they arrived at the mill, leaving behind only faint staining.

The Industry Weighs In

If you’re still skeptical, consider this: 93.6% of U.S. paper mills actively accept corrugated pizza boxes. That’s not a rounding error. That’s the American Forest & Paper Association confirming that the industry wants this fiber.

Why? Because pizza boxes are made from virgin corrugated cardboard—high-quality material that can be recycled up to seven times. At 600,000 tons of corrugated board produced annually just for pizza boxes, that’s a massive stream of valuable fiber currently being diverted to landfills because of outdated fears.

Yet only 27% of U.S. recycling programs explicitly tell residents that pizza boxes are acceptable. Another 46% accept them implicitly (they list “cardboard” but don’t mention pizza boxes specifically), which leaves consumers paralyzed by uncertainty.

So Why Does Your Bin Still Say “No Pizza Boxes”?

If the science is settled and the mills are ready, why do so many local recycling programs still ban them?

Three reasons:

- The Food Problem: Mills can handle grease. They cannot handle half-eaten crusts, congealed cheese blobs, or sauce puddles. When residents throw in dirty boxes, it attracts pests and creates genuine contamination. It’s easier for municipalities to ban all pizza boxes than to trust people to empty them first.

- Bureaucratic Lag: Recycling guidelines are updated about as often as highway signs. Many cities still reference decades-old EPA guidance that predates the WestRock study. Changing the rules requires committee meetings, public outreach campaigns, and new signage—all for a product most people encounter once a week.

- MRF Equipment Variance: While 93% of mills are equipped to handle pizza boxes, a small minority of facilities lack the screening technology to filter out food residue. If your city contracts with one of those older MRFs, the ban may be legitimate (though that’s increasingly rare).

The Practical Guide: When to Recycle (and When to Toss)

Here’s where the rubber meets the road. Based on the data from WestRock, the Recycling Partnership, and AF&PA, here’s your decision tree:

✅ DEFINITELY RECYCLABLE:

- Standard grease spotting: Those dark patches where the pepperoni sat? Totally fine.

- Minor cheese residue: If there’s a bit of hardened mozzarella stuck to the cardboard, the mill’s screening process will catch it.

- Absorbed grease: If the oil has soaked into the fiber (not pooling on the surface), you’re good.

❌ DEFINITELY NOT RECYCLABLE:

- Saturated boxes: If the cardboard is soaking wet, the grease has turned the board mushy, or you can wring oil out of it, trash it. (Think: deep-dish Chicago-style aftermath.)

- Food scraps: Any leftover crusts, sauce chunks, or toppings must be removed first. The cardboard is recyclable; the pizza remnants are not.

- The “pizza saver”: That little plastic table in the center? Remove it. It’s not recyclable and will contaminate the fiber stream.

- Wax-coated boxes: Some specialty boxes (rare, but they exist) have a wax lining. Those are landfill-bound.

The Circular Economy Angle (Why This Matters More Than You Think)

Here’s the bigger picture: if all 3 billion pizza boxes sold annually in the U.S. were recycled, they’d represent about 2.6% of the Old Corrugated Containers (OCC) stream. That’s 600,000 tons of high-quality fiber that could be turned into new boxes, paper towels, or cardboard packaging.

But there’s a twist. Recent research from Idaho National Laboratory explored using condensable solvents like dimethyl ether (DME) to extract oils and moisture from contaminated cardboard. Their findings? DME can remove grease so effectively that treated pizza boxes end up drier than virgin cardboard. The process also separates the oily fraction (which can be converted into biofuel) from the aqueous fraction (which can be digested anaerobically).

This isn’t sci-fi. It’s a real pathway toward making even the nastiest pizza boxes recyclable—turning what’s currently a waste stream into multiple value streams: clean fiber, fatty acids for fuel, and biogas from food residue.

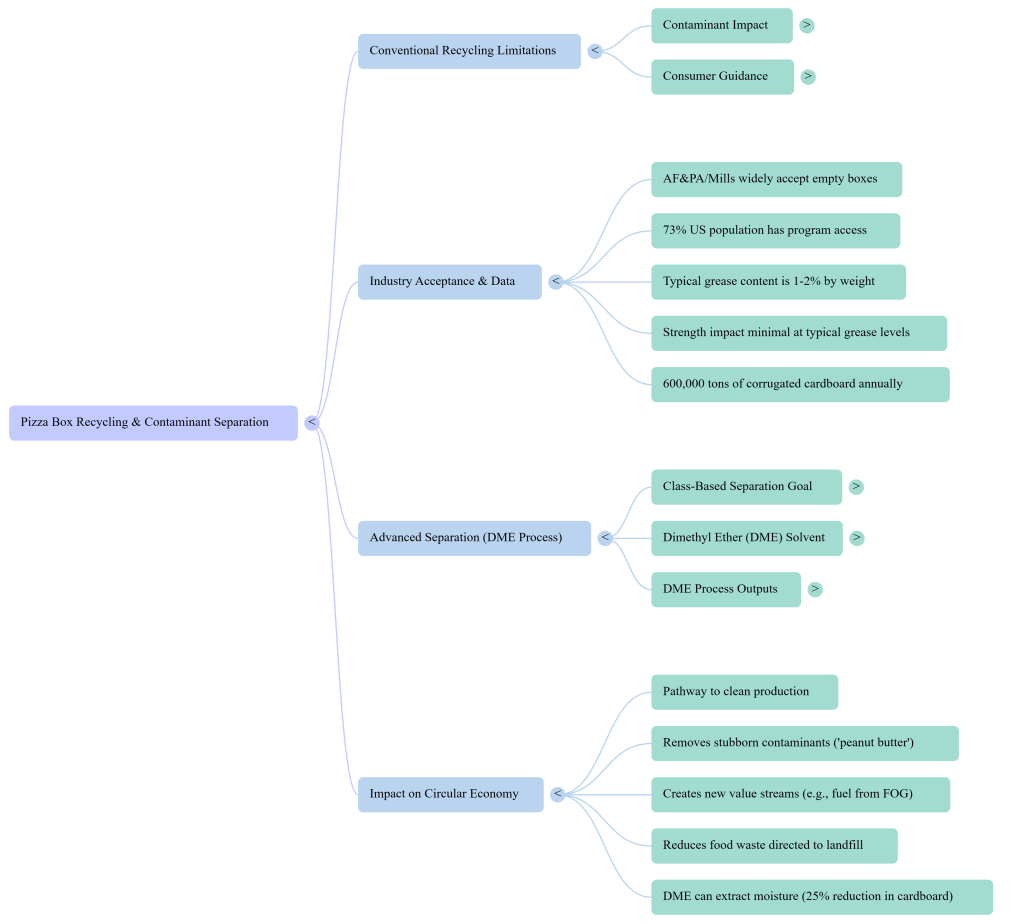

The Mind Map Breakdown

To visualize how all these factors interconnect, check out this mind map generated from the research:

The map shows four key branches:

- Conventional Recycling Limitations: Why old systems struggled (contaminant fears, unclear consumer guidance).

- Industry Acceptance & Data: The WestRock study, AF&PA endorsement, and actual grease content measurements.

- Advanced Separation (DME Process): How dimethyl ether enables a circular economy by fractionating waste into reusable streams.

- Impact on Circular Economy: The potential to recover 600,000 tons of fiber annually, create new fuel sources, and reduce landfill waste.

The Bottom Line

Can grease-stained pizza boxes be recycled? Yes—as long as you follow two simple rules:

- Empty the box completely. No crusts, no sauce, no random napkins.

- Check your local guidelines. If your city still bans pizza boxes, email your waste management department and share the WestRock study. Change happens when residents push for it.

The paper industry has done its homework. The mills are ready. Now it’s on us to stop treating that cardboard like hazardous waste.

So next time you finish a pizza, flatten the box, toss it in the bin, and sleep easy. You’re not ruining the batch. You’re feeding the circular economy.

Want to Go Deeper? Listen to the Research

For a full breakdown of the science (including the DME extraction process and molecular dynamics simulations), check out this AI-generated podcast diving into the primary sources:

Summarized podcast of 6mins

Extended detailed podcast

Sources:

- WestRock Grease & Cheese Study (2021)

- American Forest & Paper Association Industry Statement (2021)

- The Recycling Partnership Pizza Box Accessibility Study (2020)

- Idaho National Laboratory: “Class-Based Separations of Mixed Solid-Liquid Systems” (Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023)